Upper Extremity Limb Length Discrepancy

An upper extremity limb length discrepancy is a difference in the lengths of the arms. A discrepancy can be present when a child is born (congenital) or develop when a child is older as the result of injury, infection, or disease (acquired).

Most children are able to adapt to small differences in arm length and function well without treatment. Children with large differences may need physical therapy, surgery, or other treatments to help them function better and be more independent. Because significant limb differences typically develop early on in pregnancy when a baby’s bones are being formed, some children with large differences in arm length may have other musculoskeletal problems, as well.

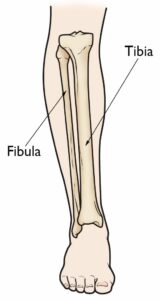

Anatomy

The bones of the arm include:

Humerus (upper arm bone)

Radius (the forearm bone on the “thumb side”)

Ulna (the forearm bone on the “little finger side”)

Most long bones in the body have at least two growth plates, including one at each end. Growth plates are located between the widened part of the shaft of the bone (the metaphysis) and the end of the bone (the epiphysis). The long bones of the body do not grow from the center outward. Instead, growth occurs at each end of the bone around the growth plate. When a child is fully grown, the growth plates harden into solid bone.

arm anatomy

Illustration shows the major bones of the arm. Growth plates are located at the ends of the long bones in children and adolescents.

Description

Children with an upper limb length discrepancy have arms that are different lengths. A discrepancy can be present at birth (congenital) or develop when a child is older (acquired). It can affect the whole limb or just part of the limb.

Cause

Congenital Upper Limb Length Discrepancy

In a congenital upper limb length discrepancy, the arm does not form normally as a baby grows in the uterus. As a result, the baby is born with an arm that is shorter than normal or is missing.

In many cases, the cause for a congenital limb length discrepancy is not known; doctors are simply not able to determine why it has occurred.

Sometimes, a congenital limb length discrepancy is associated with a medical condition or syndrome that affects multiple parts of the body.

Congenital conditions that may cause an upper limb length discrepancy include:

Radial deficiency. In this condition, the radius bone and soft tissues of the forearm fail to develop properly. This causes the affected hand to be bent inward toward the thumb side of the forearm, giving it the appearance of a “club hand.” The forearm may also be shortened. A radial deficiency can sometimes be associated with other congenital conditions and syndromes, including:

Thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR) syndrome. A disorder characterized by low levels of platelets in the blood and absence of the radius bone in the forearm.

Fanconi anemia. A disease that affects the body’s bone marrow and can result in skeletal abnormalities.

Holt-Oram syndrome. A disorder in which patients have heart problems and abnormally developed bones in the upper limbs.

VACTERL. A disorder that causes multiple anomalies including vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheal, esophageal, renal, and limb.

Radial deficiency

In a radial deficiency, the hand is turned inward, giving it a club-like appearance, and the forearm may be shortened.

Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children—Northern California

Ulnar deficiency. In this condition, the ulna bone and soft tissues of the forearm fail to develop properly, causing the wrist to bend toward the little finger side of the hand (this is the opposite direction to that seen with a radial deficiency). The severity of the condition can vary greatly from patient to patient. In the mildest cases, there may be only a mild tilt of the wrist. In the most severe cases, the ulna may be missing entirely. Patients with an ulnar deficiency sometimes have other musculoskeletal problems that affect the spine, hips, legs, and feet.

Madelung deformity. In patients with Madelung deformity, part of the radius stops growing early, while the ulna continues to grow and dislocates, leading to malalignment of the wrist joint. Some patients with Madelung do not have noticeable symptoms and the wrist deformity is not discovered until an x-ray is taken for an unrelated reason.

X-ray of Madelung deformity

In this x-ray of Madelung deformity, the end of the ulna does not fit properly with the radius, causing malalignment of the wrist joint (arrow).

Reproduced from Johnson TR, Steinbach LS (eds.): Essentials of Musculoskeletal Imaging. Rosemont, IL. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2004, p. 824.

Acquired Limb Length Discrepancy

An acquired limb length discrepancy is a difference in arm length that develops when a child is older. Causes may include:

Previous injury to a bone in the arm. A broken bone in the arm can lead to a limb length discrepancy if it heals in a shortened position. This is more likely to happen if the bone was broken into many pieces. It is also more likely to happen if the injury damages the growth plate near the end of the bone—particularly at the wrist or at the shoulder. When this occurs, the bone may grow at a faster or slower rate than the bone on the opposite side.

growth plate fractures

Illustration shows different types of growth plate fractures. An injury in this area can affect how the bone grows.

Bone infection. Bone infections that occur in growing children can cause an upper extremity limb length discrepancy. This is especially true if the infection happens in infancy and affects the growth plate.

Bone diseases. Some bone diseases may result in a limb length discrepancy. Multiple hereditary exostosis (MHE) is a disorder of bone growth in which bony bumps develop close to the growth plates. When these bony bumps form on the radius or ulna, they may cause shortening or angulation of the forearm.

Symptoms

The effects of an upper extremity limb length discrepancy can vary greatly from one child to another, depending on the cause and size of the difference. One child may have a growth plate injury that results in just minor shortening of a bone that is hardly noticeable. Another child may have a radial deficiency that results in significant shortening of the forearm. Your doctor will talk with you to learn more about your child’s specific symptoms.

To Top

Related Articles

DISEASES & CONDITIONS

Congenital Hand Differences

DISEASES & CONDITIONS

Growth Plate Fractures

DISEASES & CONDITIONS

Bone, Joint, and Muscle Infections in Children

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Your doctor will carefully examine your child’s arm, checking range of motion in his or her shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand.

If your child has had an injury or infection, your doctor will want to know when it occurred and how it was treated.

If your child has a congenital condition, it will most likely have been diagnosed soon after birth. Some cases are more complex and have more than one feature, however, and referral to a specialist may be necessary to make the correct diagnosis.

Tests

X-rays. X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor will order x-rays to confirm which bone is affected and to learn more about your child’s condition. An x-ray may also be used to measure the size of a discrepancy.

Genetic testing. An evaluation by a genetic specialist may be recommended if your child has a limb length discrepancy caused by a medical condition or syndrome

Additional tests. If your doctor suspects that your child has a medical condition or syndrome, he or she may order additional testing to determine if other parts of the body are affected, such as the heart or kidneys.

Treatment

If your child has a small limb length discrepancy and no functional problems, treatment is typically not needed unless symptoms develop. Children who have a significant discrepancy may need surgery to be more independent and participate in activities they are interested in.

Your doctor will consider many things when determining your child’s treatment, including:

The cause and size of the discrepancy

Your child’s age and overall health

The needs of your child and the goals of the family

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment may include:

Observation. If your child has had a fracture or infection involving the growth plate and has not yet reached skeletal maturity, your doctor may recommend simple observation until growing is complete. During this time, your child will be reevaluated at regular intervals to determine whether the discrepancy is increasing or remaining the same.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help strengthen and improve range of motion in the wrist and arm.

Occupational therapy. Exercise and training can help improve handwriting and other fine motor skills.

Assistive or adaptive devices. Using specialized devices can make dressing and other daily activities easier.

Prosthetics. Artificial devices can be used to replace missing parts or limbs.

Surgical Treatment

There are several surgical procedures used to treat upper limb length discrepancies. The procedure your doctor recommends—as well as the age at which the procedure is performed—will depend upon the cause and size of the discrepancy, as well as the type of surgery.

Surgical procedures may involve:

Slowing down or stopping the growth of the longer limb

Gradual lengthening of the shorter limb with an external device or a device placed inside the bone

external fixation

In this clinical photo, an external fixator is used to realign and lengthen the patient’s humerus (upper arm bone). A previous bone infection led to a fracture that healed incorrectly and caused shortening of the bone.

Courtesty of Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children

Shortening of the longer limb

Reconstruction of parts of the hand, wrist, and arm to make them appear more normal and to improve the alignment

Skin grafts to replace skin that is missing or has been removed as part of a surgical reconstruction

Recovery

How long it takes your child to recover from surgery will depend upon the specific procedure performed. During recovery, your child will have regular follow-up visits with his or her doctor and x-rays will be taken to check the healing process of the affected bone.

Physical therapy will help your child gain muscle strength and improve range of motion in the affected limb and is often required for several weeks.

If the limb length discrepancy is the result of a medical condition or syndrome, your child may have other musculoskeletal issues that require treatment, as well. Your medical team will continue to address any concerns you may have and provide the ongoing support and treatment needed to help your child thrive.

Tibial hemimelia is a partial or total absence of the tibia, which is the larger bone in your lower leg.

Description

Tibial hemimelia is a congenital condition, which means that it is present at birth. In the mildest cases, there may be only minor shortening of the tibia. In the most severe cases, the tibia may be missing entirely. Tibial hemimelia usually affects only one leg but, in about one-third of cases, both legs have the condition. When one leg is affected, it is usually the right leg, although doctors do not know why this is.

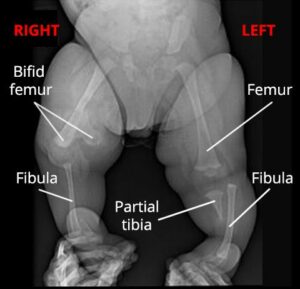

A baby boy with tibial hemimelia affecting both legs.

Reproduced from Krajbich IJ: Lower limb deficiencies and amputations. J Am Acad Orthop Surgeons 1998; 6:358-367.

Types of Tibial Hemimelia

Doctors usually divide tibial hemimelia into four different types, based on how much of the tibia is missing. Knowing the specific type will help your doctor develop the best treatment plan possible for your child.

-

- Type I. In this type, the tibia is missing in its entirety. As a result, the child’s knee and ankle joints do not usually work.

- Type II. In this type, the lower half of the tibia is missing. The knee joint usually works somewhat normally, but the ankle joint does not work.

- Type III. In this type, the upper half of the tibia is missing. As a result, the knee joint does not usually work, but the ankle joint may work somewhat normally. This type of tibial hemimelia is extremely rare.

- Type IV. In this type, the child has a shortened tibia and the lower ends of the tibia and fibula bones, near the ankle joint, are separated from each other. This causes the ankle joint to be very abnormal.

Other Medical Problems

Many children with tibial hemimelia are born with other problems involving their feet and legs, such as:

-

- A shortened femur (thighbone)

- A bifid femur (the bottom end of the thighbone is split into two)

- An absent extensor mechanism (the muscles, ligaments, and other structures that help the knee to straighten are missing)

- Clubfoot (the foot is turned inward)

- Absent toes or too many toes

Some children with tibial hemimelia may also have conditions that affect the arms.

X-ray shows a healthy 7-month-old boy with tibial hemimelia of both legs. On the right side, the bottom end of his femur is split into two (bifid femur) and his tibia is missing. On the left side, his femur appears relatively normal, but the bottom half of his tibia is missing.

Cause

Most of the time, doctors do not know exactly why a baby is born with tibial hemimelia. Occasionally, however, the condition can be passed on through a family.

Sometimes, tibial hemimelia is associated with a medical condition or syndrome that affects multiple parts of the body, such as Werner’s syndrome, Langer-Giedion syndrome, and CHARGE syndrome.

Doctor Examination

Severe cases of tibial hemimelia are usually detected before the baby is born, during a prenatal ultrasound. Milder cases may not be recognized until after birth when the parents notice a difference in leg length as their child grows.

Medical History and Physical Examination

Since tibial hemimelia can sometimes be hereditary, your doctor will ask whether your family has any known medical syndromes or if there is a family history of short tibias.

During the exam, your doctor will carefully measure the lengths and widths of your child’s arms and legs. He or she will also move your child’s legs and feet in different ways to learn more about the knee and ankle joints. The exam will not be painful.

Tests

Tests will help your doctor confirm the diagnosis and guide your child’s treatment plan.

X-rays. X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays of your child from his or her hips down to the feet to determine which bones are present and which are missing. X-rays will also help your doctor estimate the difference in the length of your child’s legs.

X-rays can be performed as soon as your child is born. Although not all of the bone can be seen during infancy, a great deal can still be learned about the shortened tibia during this first set of x-rays.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Your doctor may order an MRI to learn more about your child’s knee and ankle joints. The condition of these joints is very important in making treatment recommendations.

Genetic testing. If your child’s tibial hemimelia is caused by a medical condition or syndrome, your doctor may recommend an evaluation by a genetic specialist.

Treatment

The goals of treatment are for the child’s leg to work as well as possible, be pain free, and be as close as possible in length to the leg on the other side by the time he or she is fully grown. Treatment for tibial hemimelia involves a team of medical specialists. The team may include an orthopaedic surgeon, a pediatrician, physical and occupational therapists, an orthotist, and a prosthetist.

Your child’s treatment plan will depend on many different factors, including:

-

- How much of the tibia is missing

- How well the knee and ankle joints work

- The difference in the length of the legs

- Your child’s overall health

- Your family’s preference for a certain procedure

Nonsurgical Treatment

Almost all children with tibial hemimelia will eventually need surgery to help them function better. In very mild cases, however, nonsurgical treatment can sometimes be an option until surgery is required.

Nonsurgical treatment may include:

-

- Wearing a shoe lift. If the child’s foot can fit in a shoe, a shoe lift can help to even out a smaller difference in leg length.

- Prosthetics. For a larger difference in leg length, an artificial device can be fitted over the shorter limb to allow the child’s foot to be flat on the floor. These types of “accommodative” prostheses become more difficult to make over time, however, and then some type of surgery is almost always necessary to allow the child to walk and stand better.

Surgical Treatment

The surgical treatments most often used for the management of tibial hemimelia are:

-

- Limb reconstruction and lengthening

- Limb amputation

Limb reconstruction and lengthening. For children with less severe cases of tibial hemimelia, limb reconstruction and lengthening may be a viable treatment option.

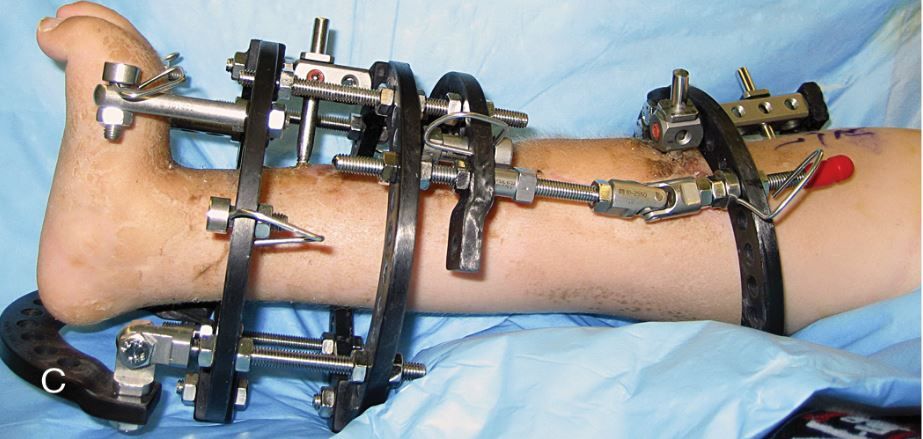

Reconstruction usually involves one or more surgeries to repair the bones, muscles, and joints that are affected by the hemimelia. This is followed by gradual lengthening of the leg using an external fixator.

The external fixator is worn until the lengthened bone is strong enough to support the patient safely.

Limb lengthening usually requires multiple operations over several years.

An external fixator may be used to gradually lengthen the shorter leg.

Reproduced from Hamby RC, McCarthy JJ (eds.): Management of Limb-Length Discrepancies. Rosemont, IL. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011, p. 134.

Photo (left) and x-ray (center) show a boy with Type IV tibial hemimelia. He has a shortened tibia and the lower ends of his tibia and fibula bones are separated, making his ankle joint very unstable. (Right) After limb reconstruction and lengthening with an external fixator, he is able to place his foot flat on the floor. He will need a second (and possibly third) procedure in the future.

Reproduced from Hamby RC, McCarthy JJ (eds.): Management of Limb-Length Discrepancies. Rosemont, IL. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011, p. 105.

Limb amputation. For many children with tibial hemimelia, limb reconstruction and lengthening may not produce the best outcome. For example, if the child has no functional ankle joint or is not able to actively straighten his or her knee (especially if the structures that enable the knee to straighten are missing) reconstruction and lengthening become more challenging.

In these situations, the best chance for the child to have an active life often involves amputation of the affected limb. After the limb is amputated, a prosthetist will fit the child for a prosthetic limb. The prosthetist will adjust the prosthesis or make a new one as the child grows.

The decision whether to opt for amputation is, understandably, a very difficult one for parents. Your orthopaedic surgeon and other medical specialists on your team will provide you and your family with support and education to help you determine which treatment option is best for your child.

Support

Living with—and having treatment for—tibial hemimelia can be both emotionally and physically challenging for a child and his or her family. Meeting other children with limb deficiencies and their families will provide reassurance that you are not alone and will be an invaluable source of information and support. You can find support and discussion groups for families of children with limb deficiencies online. In addition, your doctor may be able to put you in touch with families like yours so that you can meet and talk with them about their experiences.

Thanks to advances in prosthetics and limb reconstruction, most children with tibial hemimelia are eventually able to participate in almost any activity. It is important to help your child by being supportive and encouraging a positive self-image. If your child is struggling with either the emotional or physical aspects of treatment, be sure to share your concerns with your doctor.